Disclaimers

At the outset, a couple of disclaimers: This is not an academically rigorous demonstration. It is intended for students who have newly been introduced to deconstruction. I make statements that I am well aware may not hold up to serious scholarly challenge. But that’s okay. Anyone who has seen the WIRED magazine’s Five Levels of Explanation videos knows that communicating complex concepts requires conceding to age, education or/and relevant experience, and simplification can often be at the expense of rigour.

I do not seek here to elaborate deconstruction as a theory or strategy—if it could be characterised in these terms—but in order to explain what is going on, I will have to say a few things about deconstruction, at the risk of oversimplification. All I am looking to do is to show to English newbies how to read a poem using a deconstructionist lens.

Defining deconstruction

If I were being professorial, I would take an academically defensible route and offer a definition such as the one culled by Nicholas Royle, from the various pronouncements of Jacques Derrida, the father figure of deconstruction:

deconstruction n. not what you think: the experience of the impossible: what remains to be thought: a logic of destabilisation always already on the move in ‘things themselves’: what makes every identity at once itself and different from itself: a logic of spectrality: a theoretical and practical parasitism or virology: what is happening today in what is called society, politics, diplomacy, economics, historical reality, and so on: the opening of the future itself.1 (p.11)

When you go through this definition, it is perfectly normal to feel a kind of brain freeze. And so, in approaching the poem selected for analysis, we will skirt around this definitional black hole. Instead, we will start by saying what ‘deconstruction’ is not. It is not—according to its exponents—a theoretical toolkit that the analyst brings to a text (a poem, a painting etc) from the outside. In this respect, it is fundamentally different from all others interpretive perspectives. When structuralist, feminist, Marxist or psychoanalytic critics approach a text, they look for evidence in support of their perspective, even as they demonstrate how the text illustrates their theory.

On the contrary, deconstruction contends that the textuality of a text is essentially a facade. There is no perspective that a text can support because textual elements are actively engaged in a conspiracy against the text. As Paul de Man, a key contributor to deconstruction, suggested, a text “deconstructs” itself.

In my making is a manner of unmaking The lightening spark that (consumes) the land rises from the heat of the peasant's blood.

How does that happen? Well, that happens because the relationship between the elements that constitute a text—a poem, for example—and the significance of these elements (what these elements mean) is fraught.

Take ‘words’ as one element of poetic expression.2 What words mean is actually always built on their relationship with other words in the language. Look up the word ‘bravery’. It will take you to ‘showing courage’. Look up ‘courage’ and it will take you to ‘mental or moral strength to withstand fear, danger or difficulty’. And this coupling of word and meaning goes on indefinitely and inexhaustibly in language. The meaning of a word calls up other words. The trouble is that words almost always have multiple senses and shades that don’t sit quite squarely with the senses and shades of words to which they are tied. ‘Brave’ for instance has some secondary archaic meanings that are absent in the ‘courageous’ entry.3 ‘Courage’ suggests an inner capacity, rather than a spectacle associated with ‘bravery’. There is an element of incongruity or difference between a given word and the terms used to explain or characterise it. The contours of words do not coincide with the contours of their meanings.

Moreover, at every stage, meaning gets pushed off to other lexemes (words). The fact that a word can only signify (mean) what it does with the help of other words creates a type of ‘circular debt’ within language that each word owes to other words. Ultimately, these two realities—the growing multiplication of meanings (from word to word) and the perpetual postponement of a graspable sense wedded to a word—crush the possibility that the text could yield a stable interpretation. I started off by saying that I will avoid elaborating deconstruction. Nonetheless, take the above for what it is: a watered down elucidation of deconstruction as a theory.

The bottom line is that once it has been shown that a text is riddled with inconsistencies and contradictions, whatever the text is claiming becomes suspect.

Deconstruction in action

With the above in mind, let us get started with the deconstructionist task at hand.

We pick a poem that was published over a hundred years ago, in 1923: Robert Frost’s Dust of Snow. It is made up of a single sentence that runs over eight lines and all but two of its 34 words are monosyllabic. The simplicity of its form and the felicity of its word choice couldn't be more arresting.

Dust of Snow

The way a crow Shook down on me The dust of snow From a Hemlock tree Has given my heart A change of mood And saved some part Of a day I had rued.

Now the way this simple poem has commonly been understood highlights how an ordinary event on a glum winter day—the ruffling of feathers of a bird atop a tree—cheers up a man (standing by, perhaps, we don’t know) under the tree as the snow shaken off by the bird gets lightly sprinkled on the speaker. This is the junior school perspective.

The more mature readers would argue that there is a twist suggested by the inclusion of two dark figures in the poem: the crow and the hemlock tree.

For some fun, I asked ChatGPT for its take on the poem and here’s what it has to say about the poem:

In the poem, the speaker describes how a crow shakes the "dust of snow" from a hemlock tree onto him, which leads to a "change of mood" and saves "some part of a day I had rued" (regretted).

On one level, the poem can be seen as a simple description of a moment in nature. The speaker is walking through the woods when a crow shakes snow from a tree onto him. This event, however small, has a positive effect on the speaker's mood, which he describes as a "change of mood".

On another level, the poem can be interpreted more deeply. The crow and the snow can be seen as symbols of death and sorrow. The hemlock tree is associated with death and poison, and the snow can be seen as a symbol of coldness and lifelessness. Despite this, the speaker is able to find some beauty in the moment and turn his mood around, suggesting that even in the midst of darkness, there can be hope and redemption.

Overall, the poem is a short and simple yet powerful meditation on the power of nature to change our moods and our perspectives.

As sophisticated as Aritifical Intelligence can get, the final statement generated by ChatGPT is a signature move in virtually all varieties of literary analysis: some definitive claim about the meaning of a work or a statement of evaluation.

Ordinarily, the goal in literary analysis is to establish with the help of intrinsic (textual) or extrinsic (contextual) evidence that the work in question is on some literary (or ideological) criteria “successful” i.e. good or “unsuccessful”. But if we are wearing the deconstructionist hat, the goal in analysis is to show that it is impossible to grasp the poem because of the nature of language, more specifically because of the non-committal ‘attitude’ of the resources of meaning.

Unlike most literary criticism, a deconstructionist reading is not looking to explain whether the poem ticks or sucks. The theory insists that a literary work comes, so to say, pre-installed with features that disillusion the close reader from any interpretation of the work.

Without further ado, here we go with the deconstructionist reading of the poem. To start with, note the title of Dust of Snow: There is a minor oxymoronic tug between ‘dust’ (which is always in the form of particles that are subject to scatter) and the coalescing and congealing properties of snow. Further, in ordinary life, ‘dust’, 'snow' as well as the 'dust of snow' are sources of inconvenience. To be clear, we are not considering scientific experiments or sight-seeing tours, where these objects of nature may conjure neutral or even positive associations. In everyday human experience, ‘dust’ and ‘snow’ are realistically speaking unwelcome. However, the story in the poem flips this experiential fact on its head. A little 'dust of snow' becomes a mood-lifting catalyst.

Now this beautiful irony about the extraordinary power of the ordinary in nature is often the centrepiece of commentaries on the poem. But deconstructionists may trouble this observation by drawing attention to a few facts from the poem. For one thing, they would point out, it is not the dust of snow as such that is ‘therapeutic’. It is the way that the crow had shaken down the snow that according to the poet changes his mood. And at any rate, because we cannot presume intentionality on the part of the crow, or for that matter the lack of intentionality—we cannot talk to the crow and confirm—we cannot be too sure about the “dust of snow” as the “efficient cause” of the emotive transformation (change of mood).

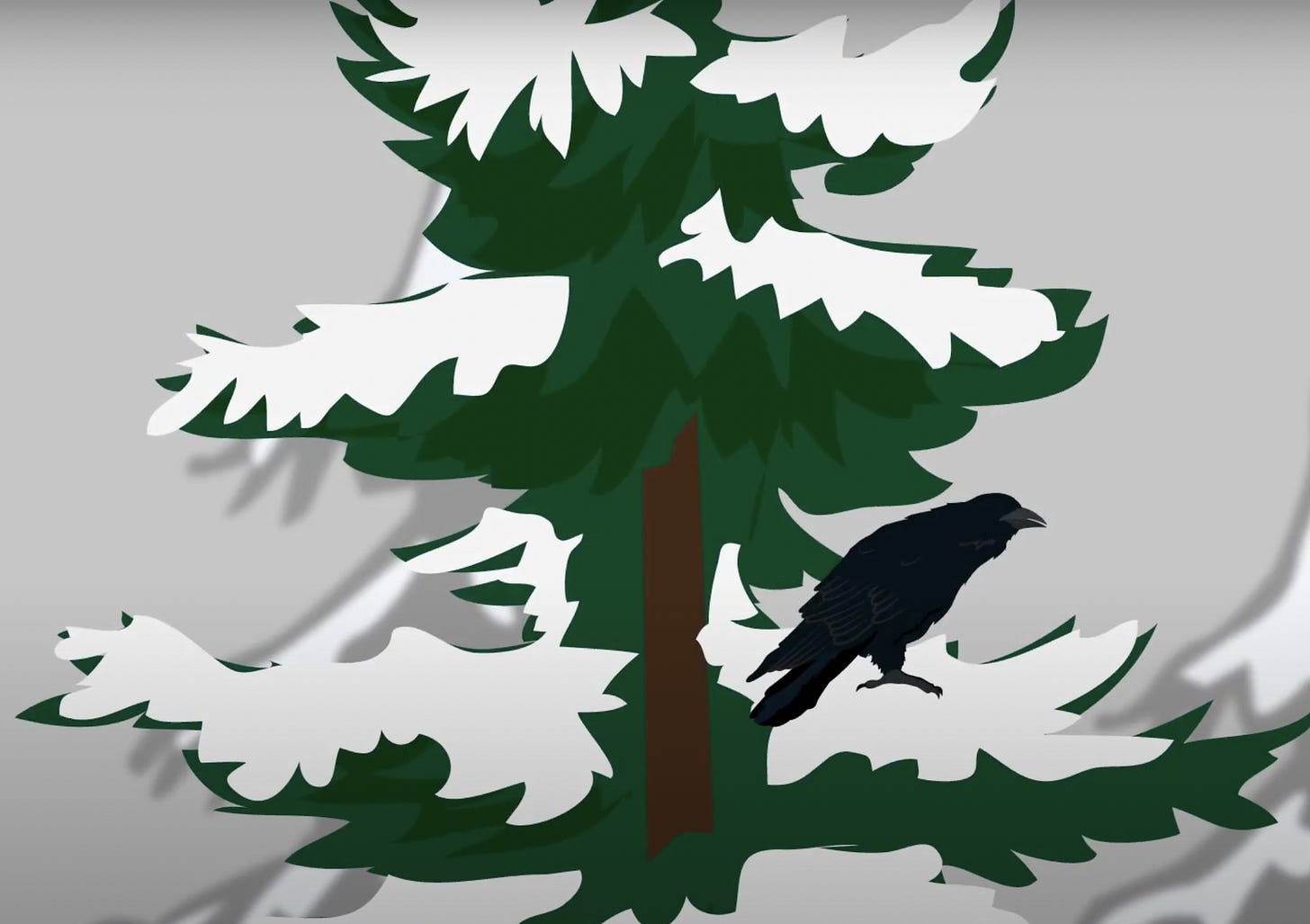

Moving on, the first character in the poem is that of the crow. According to Crow Symbolism: A Complete Guide, in western literature and mythology, associations with the crow are both positive and negative. Crows symbolise bad omens and death and by extension the pastness of the past; at the same time they also signify wisdom, foresight and destiny, which belong to the future. The acute ambivalence of the crow puts the poem in a rhetorical tailspin and we will see how shortly. But what creates another difficulty within the same stanza is the second character viz. the hemlock tree, which is equally ambivalent in terms of what it signifies.

In popular imagination, hemlock is identified with the highly toxic European plant of the parsley family. As such, hemlock stands for the death of wisdom (cf. the poison that Socrates drank) and if the crow (a sign of intelligence) is perched atop the very source of morbidity (the poisonous tree), a dark sickliness overshadows wisdom (often symbolised by light). This deeply cynical notion of wisdom is relevant because it throws into sharp relief the intelligence of spontaneous joy that nature provokes—which the subject matter of the poem seems to be about, on the surface at least.

To go back to the hemlock tree, all of our interpretive karate chops are based on what is called hemlock in Europe. In North America, where the poem has actually been written, hemlock is an entirely different non-poisonous tree. It is usually a very tall, evergreen conifer and presented in the American culture as a symbol of health, healing, security and longevity.

Four lines or 16 words into the poem, serious contradictions are already pulling at one another. At one level, we should be wondering: Is it a good sign that the crow is sitting on a hemlock tree, or a bad sign? But that is not what deconstruction as a theory aspires to answer. What is simply happening—the theory would say—is that a close reading of the poem is bringing the reader to a deepening awareness of something that was already there in the poem.

Deconstruction does not at all imply any disassembling of the text itself. Yet what does happen the moment we use the deconstructionist lens is that cracks begin to emerge in the prevailing, preferred or default understanding of the text.

Now back to the poem: The second verse paragraph begins mid-sentence in continuation of the opening sentence. It begins with a verb in the perfect tense: “has given”, one of two main verbs in the poem.4 The spotlight on this verb phrase (aux. ‘has’ + main verb ‘given’) may be significant to other analytic approaches for their own reasons but from a deconstructionist perspective, there are two things striking about this phrase: one grammatical, the other lexical.

Grammatically speaking, a verb in the perfect tense implies recency of the action denoted by the verb, and this immediacy at least in some situations may suggest that the action is reversible. That in effect may lend a certain tentativeness to the action associated with the verb.

In the poem, the role of the verb “give” is pivotal to any interpretation of this poem because essentially it is this verb that describes the central action taking place here. But the action takes place in the immediate, momentary past expressed in the perfect form of the verb. This grammatical tense sits on a temporal borderline that somewhat compromises the categorical certainty of the associated action. By contrast, a verb in the past simple (which signifies remoteness) is bounded and foreclosed to any possibility of change.

This brings us to the lexical side of the verb phrase. To quote it in context:

Has given my heart/ A change of mood

As any competent speaker of the language can bear out, the collocation ‘give x a change’ (where x could be anything) does not exist in the English language! If we want to describe a change caused by something, we say ‘a’ changed ‘b’. The expression (‘give x a change’) makes the truth being asserted here dramatically questionable. The idiomatic awkwardness of the two lines quoted above marks stylistic formality—a lack of felicity and authenticity that otherwise characterise the piece from the start to the end.

Plus, to say that the heart was given a change of mood is not just foot-in-the-mouth language. In the social universe of the poem, the grammatical structure makes the heart a passive receptacle of feelings (‘has given my heart a change of mood'); yet in spite of its weakness, the heart is made to hold up the full weight of the transmutation of mood.

One other observation urges notice. It has to do with the the trajectory of the tense system operative in the poem. Setting aside the fact that two out of the four verbs in the poem are actually syntactic constituents of the single sentence that forms the entire poem: ‘Shook down’ is part of the full subject and ‘rued’ is part of the grammatical object of the sentence, the central action is in the present perfect (‘has given’).

The collocational oddness and the tentativeness associated with the tense have already been noted. What is problematic here (see the figure below) from the deconstructionist angle is that despite its weakness, the action emblematised in the present perfect manages to dislodge a prior action that is firmly secure in the past perfect: “had rued” is remoter than ‘saved’ and far more more sensorily concrete than “give” (‘has given my heart a change’). Even so, the vulnerable verb phrase is asked to pull off the transformation that the poem is about.

It is important to recognise that the above remark is not a comment about the success or failure of the poem. The observation is intended to bring out another system of counter-pulling forces subverting the text.

To sum up, a deconstructionist analysis rests on the argument that any generalisations about the meaning of the poem—that this poem is about the efficacy of nature; or about how irony and paradox inhere ordinary experience; or about human impulsiveness etc—are only as good as distance from the text would allow. The closer we approach the text, the more we are mystified. The sounds, the words, the propositions, even the punctuation signs within a literary work conspire to undermine any confidence we would like to feel about the meaning of the work. As Max Meyer once said:

The whale has a twofold distinction among the fishes: first, when seen from a distance, it looms large among them; and second, on close examination it is found to be no fish at all. Royle, Nicholas. "What is deconstruction?." Deconstructions: A user’s guide (2000): 1-13.

There are other elements too—sounds, propositions, punctuation—but words are the core building blocks.

“Brave.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/brave. Accessed 28 Feb. 2023.

There are in fact four verbs in the poem but two of those are embedded within noun phrases: shook down and rue.